The gaze of the outsider

by Bas Heijne

Distance and engagement in Hans Wilschut’s photographs, these emotions cease to be each other’s opposites. Time and again, he seems to step back, deliberately removing himself from the scene, precisely in order to come closer, to pierce to the core, to see even more acutely. He avoids our gaze, emphatically refusing to take our perspective. He is the outsider who compels us to look again, who infuses the banal and deathly world with unanticipated new life. His work deliberately heightens the tension between the outsiders perspective and his engagement with the world around him.

This tension is well known to us, like a thread running through the history of art.

About two thirds of the way through Dostoyevsky’s novel The Idiot (1881), the story is interrupted by a passage that might be called an intermezzo, were it not so disturbing. Ippolit, a young man in the terminal stage of tuberculosis, with death written on his wasted features, reads what he calls an Essential Explanation to the assembled company, among whom is Prince Myshkin, the ‘idiot’ of the title. In his confused, emotional outpouring, the dying Ippolit rails against the prince’s attempts to lessen the pain of his final days by caring for the young man in his country home, so that he can draw comfort from the beauties of nature. Ippolit seems to consider this prospect a cruel humiliation: “What use to me is your nature, your Pavlovsk park, your sunrises and sunsets, your blue sky, and your contented faces when all this endless festival has begun by me being excluded from it”(translation by Constance Garnett).

The truths that young Ippolit utters are harsh ones. This parting leaves no room for consolation. The dying man is a protest against the world itself, which has casually distanced itself from him.

Dostoyevsky’s idiot, whom he sees as representing the ‘truly good man’, is deeply distressed by the accusations of the dying boy, who follows his long speech with a clumsy suicide attempt. His ranting reminds Myshkin of a similar feeling of alienation that he once had when under treatment in Switzerland. One brilliant day, the prince had been walking in the mountains, admiring the sun-drenched landscape, when suddenly he felt terribly distressed. He extended his hand to the ‘infinite blue’, as the tears ran over his cheeks. ‘What tortured him was that he was utterly outside all this. What was this festival? What was this grand, everlasting pageant to which there was no end, to which he had always, from his earliest childhood, been drawn and in which he could never take part?’

The emotion is as extreme as it is familiar. Prince Myshkin is the eternal outsider, the man who feels that he plays no part in the world around him. Dostoyevsky’s entire novel can be read as his attempt to connect to the world, to make contact with the things he sees around him, to take part in ‘the human community’ an attempt that is doomed to failure.

But society needs him, and that is the other side of the story. Precisely in his role as an outsider, the prince becomes a kind of conscience of the community from which he is excluded. For the other characters in Dostoyevsky’s novel, Myshkin ‘the holy fool trying to find his way in the world, stumbling toward his tragic fate’ figures as a moral force that lies beyond their reach, by turns admired and hated, praised and derided, but never to be denied. He moves among them, brushes up against them, but is not one of them. His inability to be part of their community is, in fact, his strength.

This theme ‘the outsider with the potential to regenerate a morally debased society’ has enormous resonance in art, reverberating throughout the nineteenth century. For the composer Richard Wagner, it swelled into an obsession. Wagner’s operas, from Der fliegende Holländer (1843) to his final work, Parsifal (first performed in 1882, a year after the publication of The Idiot), always revolve around a man doomed by fate and his origins to stand outside the conventional order, and a community yearning for redemption.

The Wagnerian outsider ‘whether he is the Flying Dutchman, the mysterious knight Lohengrin, the Minnesinger Tannhauser, or the aspiring Meistersinger Walther von Stolzing’ needs the community in order to realize his full potential, or even, like the Dutchman and the Grailseeker Parsifal, to find redemption. At the same time, the community is consciously or unconsciously in search of the outsider who brings the hope of a new and better life. Every one of Wagner’s operas could be seen as a renewed attempt to achieve the impossible: the individual as an artistic and religious force, searching for a place in human society. Only at the end of Wagner’s last opera, Parsifal, does redemption finally occur, when the ‘holy fool’ Parsifal brings the Spear back to the Grail. The outsider and the community come together. No longer is there any distance between them. This utterly divine conclusion was soon recognized, by Friedrich Nietzsche, as a sublime lie, pseudo Christian in character, as seductive as it is treacherous.

In reality, the tension between individual and community remained unresolved. For in the final analysis, all the artistic parables about lone outsiders and communities longing for redemption expressed a basic human truth: at some point, a group or society always becomes lost in its own world, unable to see or alter itself, in need of an outsider to bring about change. At the same time, a free individual is always in search of something larger than himself with which he can identify a community.

In nineteenth century novels and operas it is often the solitary artist ‘the poet, the painter, or the sculptor’ who represents the outsider, the man of superior in-sight. Because Christianity had gone into irreversible decline, the desire for transcendence was transferred to art, which was expected to take over the role of religion. The artist was prophet and Christ in one, an isolated figure, often misunderstood and mocked. Great art held out the promise of redemption, even if it was only redemption in this world.

The great artistic pioneers of the nineteenth century were also the great tragic failures, the holy fools who beat their heads against the wall of reality. The adolescent Rimbaud used his art as a battering ram against the social order. In his ‘letter from a seer’ to his teacher Georges Izambard, he wrote without a shadow of a doubt: “Now I lead as debauched a life as possible. Why? I want to be a poet, and I am working on becoming a seer”. The point is to reach the unknown through the derangement of all the senses. The suffering is tremendous, but you have to be strong, a born poet, and I have discovered the poet in myself.

When he saw that his poetic assault was doomed to failure, he abruptly stopped writing poetry, began wandering the world, and spent his final years as a trader in East Africa. He was still an outsider, but without any vision of renewal. All he had left was a radical loneliness.

The two other legendary loners of Rimbaud’s day, Friedrich Nietzsche and Vincent van Gogh, strove (each in his own way) towards a radical transformation, Nietzsche of the moral order, and Van Gogh of the dominant visual order. Both ended in despair and isolation. All three men combined a drive for radical innovation with an intense desire for community, followed (at least in Rimbaud’s case) by violent rejection. Yet even though they themselves saw their all consuming struggles as unsuccessful, later generations have viewed their tragic defeat as the very proof of their genius.

While they may not have changed the world in any lasting way, they did brush up against it. With their gaze, their words, their visions. The world was not made new, let alone redeemed, yet it would never be the same again.

The mythical proportions that their lives later assumed, and their efforts to transform society permanently, from the outside, created an image that has remained potent in our culture: the artist as the necessary outsider.

For a long time now, we have no longer expected our outsiders to believe in radical transformation. That would strike us as absurdly pretentious. Art has no power over the world. Attempts to make a real impact, to achieve true change and renewal, almost always give rise to impotent bombast, shortlived spectacle, and superficial sensationalism. Artists’ attempts to escape the isolation of the gallery and museum and ‘at a different level’ to escape the distance created by form, can be seen as an extension of the idea that art can bring new life to a society. Public space itself becomes a work of art; the distance between the work of art and the public is eliminated; and the viewers become part of the artist’s vision. They are forced to consider their relationship with the world around them from a new perspective. Public art of this kind can give rise to playful and eye opening experiments, but it is reasonable to wonder whether it truly closes the gap between art and the world. It may solve the problem of space, but not that of time; most such projects are limited in duration. Ultimately, the work of art is a performance that comes to a close. Its effect tends to be merely that: an effect.

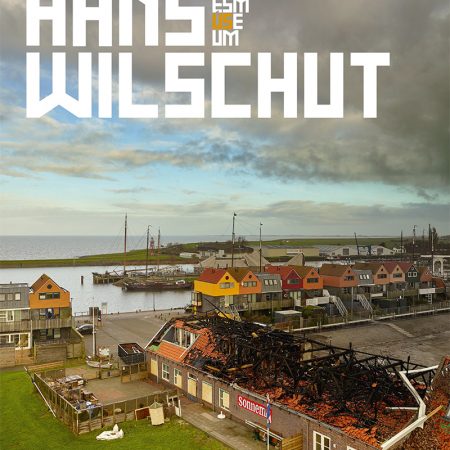

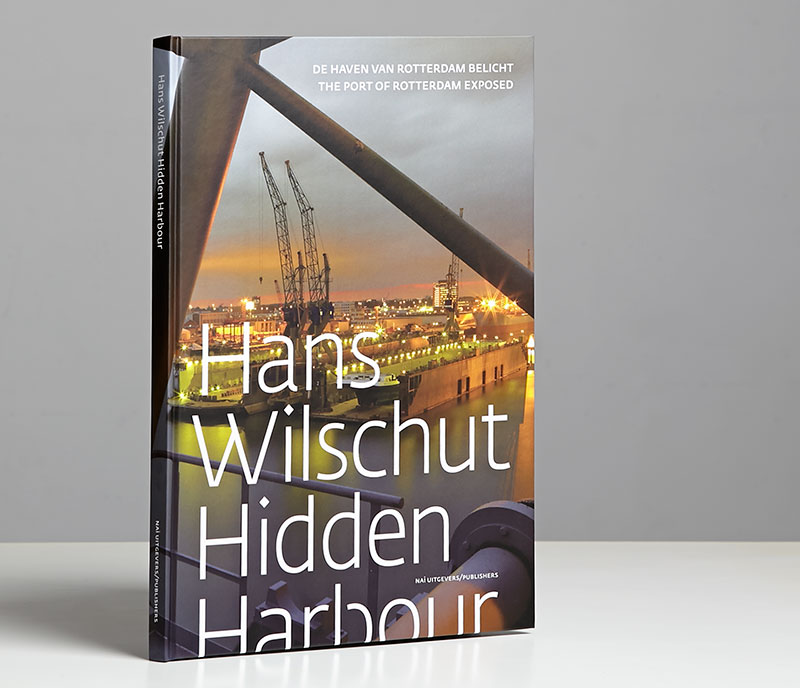

Unlike socially engaged art, the work of Hans Wilschut aims for distance. His photographs -including those of the port of Rotterdam- are always taken from an almost impossible angle, a position that we could never take ourselves. His vision is emphatically not our own.

His pictures also emphasize distance in a different sense; in his urban land-scapes, there is not a human being in sight. This is not to say that they seem depopulated. Distance, in this case, is not disengagement, and Wilschut’s cityscapes are anything but hushed. In fact, the distance maintained by the photographer makes us conscious of the continual motion around us, the manic activity that devours our lives. The presence of the human is palpable in all these photos. Everything in them was made and manipulated by human hands. Everything is in motion.

You might well call it a formidable reversal: Wilschut confronts us not with ourselves, but with the things we have created. His photographs show us just what we are up to a unique experience, since the fact that we are part of the world around us, absorbed in our activity, normally rules out any form of supervision. Day after day, we worry about society, writing opinion pieces, watching televised debates, but we are barely able to see ourselves. On the contrary, more and more words and images stand between us and the world. The harder we work to influence our society, the less capable we are of truly seeing it. And as more and more world washes over us, we are less and less capable of seeing that.

What Wilschut has in common with his nineteenth-century predecessors is that his art is a confrontation with society. His work demands consciousness; it wants to have an impact in the world. But he does not seem to be in search of radical renewal. We find no social protest, no humanistic appeal to our sense of responsibility for others, and no recriminations for the mess we so often make in the name of civilization.

His subject is more distant and, at the same time, more fundamental: it is our relationship with the world around us. Hans Wilschut defines community in terms of common property: look, this is what we have made. And the extraordinary thing about his work is that, precisely because his pictures are devoid of human presence, he achieves in a new way what art has so often sought to achieve a new relationship between the individual and the community. For here lies the paradoxical power of distance in Wilschut’s work: the things we have made, our highways, cranes, and highrises, storage centres, conduits, and containers, ultimately show us our own image.

Our distance from the world, which drove Dostoyevsky’s prince to such despair, has now been eliminated. All of a sudden, distance and engagement are one. Our vision is renewed. We see ourselves.

* translation Lourens Reedijk

text Bas Heijne translated by David McKay